Showing posts with label hip-hop. Show all posts

Showing posts with label hip-hop. Show all posts

#45 - T.I.'s "King" (2006)

Back in 2003, Michael Caine was on a press junket publicizing his then-current project, Secondhand Lions. In the movie, he and Robert Duvall are a pair of geriatric action heroes living in Texas, when they are forced to play nursemaid to their 14-year-old nephew (Haley Joel Osment). In an interview on Late Night with Conan O'Brien, the very British Caine explained how his accent coach helped him achieve his character's impressive Lone Star lilt. He said that the King's English has a stiff, upright pronunciation. Think of someone with good posture in a heavily starched shirt. The Texan, on the other hand, 'llows his words to lay down on top o' one 'nother like they're jes settin' a spell. Caine's demonstration provided not only entertainment, but also some homespun wisdom about the intricacies of regional dialect patterns. Certainly there is something inherently musical about southern speech, with its prolonged drawl and lazy cadences. Indeed, nowhere is the hip-hop concept of "flow" used quite so instructively as when describing southern rap. Pharrell once described T.I. as the "Jay-Z of the south," but listening to King, I admit I didn't quite see the connection at first blush. Then it dawned on me that while the two artists share a background in drug dealing, what really unites them is delivery. One of Jay-Z's strengths - among many - is his otherworldly ability to rhyme words that on paper have no business rhyming. No ready-made example springs to mind at the moment, but, depending on the context, he could make a word like "car" line up with "there" in one verse and "her" in the next, without allowing such enunciative license to undermine the structural foundation upon which his lyrics are built. T.I. takes this effect and applies it to whole lines, bending them at will. Plenty of rappers are "lyrical," in this sense of the word. 2Pac, Snoop Dogg, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony - all benefited from their sing-song styles. And "rapping to the beat" has been standard operating procedure since Wonder Mike. But T.I. does something extra. He doesn't rap over a beat so much as he raps in it. There's a peculiarly chameleonic quality to the way his voice takes on the shape of its surroundings, whether it's the sound of a Blaxploitation soundtrack ("King Back"), 90s dance club boilerplate ("Why You Wanna"), or the quiet storm of contemporary R&B ("Live in the Sky"). Perhaps his most impressive shape-shifting feat is coming off like the third member of OutKast, his fellow Atlantans, on "I'm Talking to You," where his pace on the last verse threatens to overtake the beat itself, having long since left most listeners behind. Grade: B+

#32 - Lil Wayne's "Tha Carter III" (2008)

I am a latter-day convert to Weezyism. Having abandoned most of hip-hop and much of other music for several years, it was only relatively recently that I began taking an interest in some of last decade's luminaries. When it came to my students, Lil Wayne was a universal favorite. They might have been temporarily distracted by the latest dance craze from Soulja Boy, but, at the end of the day, Weezy was it. The last man standing after others had been laid low by jail (T.I.), corporate stewardship (Jay-Z), revelation of artistic mediocrity (50 Cent), Auto-Tune/public humiliation (Kanye West) and drug-fueled, self-imposed exile (Eminem). Of course, nominating yourself "Best Rapper Alive" under such circumstances is akin to declaring yourself a team's biggest fan in an empty stadium after the game. Simply put, Lil Wayne was wearing a crown that nobody else seemed to want. That is not to say he doesn't deserve it. Only that we'll never truly know. How would the great Satchel Paige have fared against an integrated major leagues in his prime? The possibilities are enough to make your head spin. But, more troubling than Lil Wayne's assertion of supremacy is his paranoid style, an unfortunate extension of the hyperbolic narcissism that has come to dominate American rap. Finding it lonely (and unchallenging) at the top, much of his lyrical content is devoted to tussling with imaginary foes. "They" say Lil Wayne's a bad influence. "They" say he's addicted to cough syrup. "They" say he's lost a step. OK, but who are "they"? Pundits? Politicians? Journalists? Internet commenters? Maybe. Whoever they are, they aren't anyone who could feasibly exert a negative influence on his career. In fact, in the case of the pundits and journalists, one could argue that the publicity they generate, however negative, is invaluable. Teenagers like nothing better than music that pisses their parents off. As far as everyone else, who doesn't love an underdog story (see: New York Mets, The) even when the odds against which the underdog struggles are either unequal to the task or altogether nonexistent (see: New York Mets, payroll of). So for Lil Wayne's ego to be as big as it is, he needs to inflate these strawmen accordingly. And thus you get a long, nearly incoherent diatribe against Al Sharpton on the Tha Carter III's closer, "Don't Get It." By railing against every perceived slight, however insignificant, what is meant to be a show of strength reveals only raw nerves and a glass jaw. Eminem, too, is especially guilty of this hypersensitivity. It is duplicitous to say "I don't give a fuck" in one breath and then take on all comers in the next. To construe every critique to be an ad hominem attack, to treat all resistance as an existential threat - even figuratively - is, at best, overly compensatory. At worst, it's indicative of delusion too deep to fathom. The hardscrabble, something-from-nothing, ashy-to-classy story arc permeates hip hop so thoroughly that rap stars continue to push the line long after they've made it. They're so emotionally invested in their own Horatio Alger rags-to-riches narrative that losing success is a prospect tantamount to having never achieved it in the first place. Ironically, Weezy would have a surfeit of genuine obstacles to overcome without these bogeymen; it's just that the largest of these is himself. Consider his prolificacy. Lil Wayne's mixtapes and guest spots are legion. To the casual observer, it would seem that he is either recording tracks or else he's asleep. This type of output might have been necessary in helping him to hone his skills (we're talking about practice!) or to vault his celebrity into the stratosphere. But, at this point, it serves only to decentralize his artistic control, dilute his best ideas over too many songs, and further divide his already hopelessly splintered attention. Lil Wayne has always had more talent than taste, but imagine how good he could be if he refused to commit sub-par performances to tape? His verse on last year's Distant Relatives was easily the weakest moment on the album, an appearance that underscored how substantive was the vision of Nas & Damian Marley and what happens to Lil Wayne when he's spread too thin. As far as one-liners are concerned, he is rap's Henny Youngman. And, on that basis, he may indeed be the "Best Rapper Alive," the Usain Bolt of hip-hop. But true legacies require marathon runners and when it comes to endurance, "Weezy" is a perfectly appropriate nickname. The longer the format, the more conspicuous his flaws become. Pick any song on this album and you will most likely hear a line that makes you laugh and a line that impresses you. But, taken together, it's really just a compendium of brilliant non-sequiturs, full of sound and fury, spouted by a weed-addled savant so hooked on phonics he can't see the raps for the rhymes. Grade: C+

#22 - Lauryn Hill's "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (1998)

Alright, class, here's a word problem. Q: If a train could travel from South Orange, NJ to the banks of the Nile River, the court of Menelik II, and Kingston, Jamaica using 16 tracks, while managing to complete the trip in a little over 77 minutes with a 23-year-old conductor, how many Grammys would it win and how many albums would it sell? A: 5 and - eventually - more than 10 million. The conceit that provides the thematic structure to The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is a discussion taking place in a middle school classroom. After the introduction, during which the teacher, taking attendance, finds "Lauryn Hill" absent, each iteration of the class is tacked on to the end of one of the album's remaining fifteen songs. There is nothing terribly profound about the discussion, except for the degree to which the students and teacher are animated while talking about the subject of the day: love. The implication, of course, is that Hill, not present, is missing out on a fundamental lesson about life. A lesson she will eventually learn the hard way. Given this set up, the songs themselves become a platform from which the precocious singer and rapper may disseminate her hard-won wisdom. If this sounds like it might get preachy, your instincts are probably right. Occasionally, as during the chorus of "Forgive Them Father," Hill falls victim to believing her own hype as a messianic pop star. Elsewhere on the album, less overt attempts at creating hip-hop with a conscience fare much better. Especially during the all-too-rare rap verses, which are consistently weapons-grade. I am hard-pressed to remember any other female MC in the last 10+ years who conveyed such substantive content so eloquently or so engagingly. Given the run-time of Miseducation - which is actually a double album, longer even than Blonde on Blonde - it is impressive how little filler there is. Some of the R&B tracks drag a bit, but Hill finishes strong with two wonderfully understated performances. The first is a cover of Frankie Valli's "Can't Take My Eyes Off Of You," which sounds both modern and timeless and the second is the gospel lullaby closer, "Tell Him," with its lilting, lulling strings. Across the board the production values have held up very well, thanks in large part to the organic, rootsy contributions by New Ark, Hill's mostly live, in-studio band. Too often hip-hop is doomed by a kind of planned obsolescence stemming from a short-sighted preference for trendy studio gimmickry (Auto-Tune, anyone?). The rapid stylistic turnover encouraged by a chew-'em-up-spit-'em-out singles-driven recording industry perpetually questing for the "next big thing" may make for good business, but it also results in disposable music. Luckily, Ms. Hill & Co went in another direction. It made the difference between ephemeral art designed to move units and something that will stand the test of time. Somehow Miseducation pulled off the feat of being a classic that sold really well. Hopefully new artists are taking notes. Grade: A-

#6 - Nas & Damian Marley's "Distant Relatives" (2010)

It was hard to know a year ago what rap in 2010 would be like with Lil Wayne in jail. Aside from maybe Rihanna, there really has been no single figure in hip hop quite so ubiquitous in the last five years as the Poet Laureate of Hollygrove. I am happy to announce that the state of our union is strong. Perennial heavyweights like Big Boi, Eminem, The Roots and Raekwon all punched out strong albums this year, while newcomers like Nicki Minaj and KiD CuDi delivered full lengths that were highly catchy, if a bit more superficial in content. And though there were a few tracks still peddling in Auto-Tune, it appears as if most of hip-hop took Jay-Z’s “D.O.A.” for the coup de grace it was meant to be. Of course, all of the regular tropes are still there: the sex, the money, the braggadocio. But there seems to be more room in rap these days for realistic introspection. Or, in the case of “distant relatives” Nas and Damian Marley, a thoughtful reflection on a tumultuous past and a hopeful future. The story of Africa is the focus here – its anthropology, its diaspora, its colonization – told through a riveting and tasteful sampling of its contributions to world music. And though the album does not shy away from the well-plumbed depths of slavery and racism, neither does it wallow in anger or despair. Distant Relatives is ultimately about shared experience, a “big picture” album that insists on considering history from an inclusively human and humane perspective. Grade: A-

Subjects:

2010s,

Damian Marley,

Grade "A-",

hip-hop,

Nas

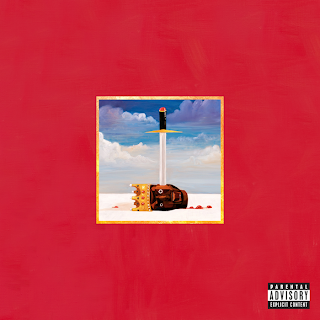

#4 - Kanye West's "My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy" (2010)

My introduction to this album’s material was watching Kanye West perform “Runaway” on the MTV Music Awards. After a year of embarrassing outbursts, interviews, tweets and an involuntary cameo on South Park, calling himself a “douchebag” felt like too little and too late. It also felt appropriately tasteless. Hearing the word “douchebags” sung, no matter how deserving its target, no matter how pretty the accompanying melody, for any reason other than comedy just felt…silly. Watching that on TV, I really thought I was witnessing Kanye nuke the fridge. But then: a pair of revelations. The first was this album, which, for all its bombast, is nearly a masterpiece. The second was my realization that his personal life – even his frighteningly narcissistic insistence on living the majority of it in public – is kind of irrelevant to the art he’s creating. I don’t want to make a virtue out of vice, but he seems capable of an alchemy that turns shit into gold. After all, reasonable people can agree on all the available facts and still disagree on the conclusions one could reach from them. Is Kanye obnoxious? Garish? Self-involved? Arrogant? Yes. Is he also charismatic? Ambitious? Self-critical? Talented? Yes. As he rightly dares us on “Gorgeous,” “act like [he] ain’t had a belt in two classes.” In 1994, major league baseball went on strike. I was 15. Turned off by what seemed to me then to be the greed of players and owners alike, I stopped watching. I even stopped playing, so great was my disgust. But, after reaching adulthood, I came back to the sport, acknowledging that the game itself was better than the men who played it. So it is with Kanye. Grade: A-

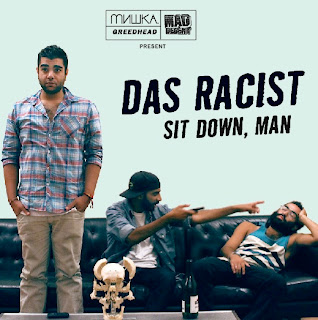

#2 - Das Racist's "Shut Up, Dude" / "Sit Down, Man" (2010)

The conventional wisdom about Das Racist is that they are not so much a rap group as a group of guys who love rap. And that this love has led to a knowledge so encyclopedic and a sensibility so epicurean that they almost can’t help being great rappers themselves. This critique is codependent with the other standard line on this band: that if they are not exactly novelty musicians (think: “Weird Als” for the millennial generation), they are, at least some of the time, taking the piss. I am of the opinion that many reviewers have missed the mark here, that they have revealed the extent to which their ideas are trapped in a kind of hipster lockstep. If for most of your adult life you have only been amused by irony, then you run the risk of believing that every time you laugh it must be the result of something ironic. Now, don’t get me wrong. Das Racist are funny. And they are not above poking fun of rap’s clichés and excesses. But that, too, reveals their devotion to rap’s legacy of humor and authenticity (see: De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, etc.) as opposed to a tongue-in-cheek aesthetic mocking rappers who take themselves too seriously. Bottom line: if you love wordplay, classic hip-hop, pop culture, good beats, self-deprecation and social commentary, then these two excellent mixtapes are as real as it gets. Grade(s): A- / A-

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)