Time

Well, as you can see, I'm way behind on my daily posts. A couple of weekends away from home and that's all it took to derail this train. Not abandoning this project; it's already introduced me to some great music and given me new directions to pursue. But I am going to put it on hold until I can give it the attention it deserves. Hopefully you've enjoyed what you've read. I've enjoyed what I've heard.

#64 - The Supremes' "Where Did Our Love Go?" (1964)

Applying the term "girl group" to The Supremes, though technically accurate, comes off dismissive when you're talking about the most successful American act of the 1960s. So many things had to go so right for this album to sound so good that lumping them in with all of the one-hit wonders and copycats is a disservice not only to the talent of Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard, but to the vision of Berry Gordy, the songwriting of composers like Smokey Robinson, and the priceless contributions of the woefully anonymous "Funk Brothers," Motown's in-house session band. While much media grist has been made of the internecine strife between the group's members, there is less than no evidence on these recordings of their inability to harmonize, literally or figuratively. In addition to the well known title track, "Baby Love," and "Come See About Me," the girls tear it up on Robinson's "A Breath Taking Guy," closing out the song by taking turns on the lead. And how about the uncredited guitar work on "I'm Giving You Your Freedom"? It starts out with just some simple plucking and gradually becomes more sophisticated as it bubbles up through the vocals. But no one outshines Ross, whose honey-dipped voice sets the tone for every single song. With singers like Tina Turner and Aretha Franklin about to come through the pop pipeline in the mid-60s, it's remarkable to hear a front-woman who opts for seductive restraint over unbridled power. Diana Ross & The Supremes make love, not war. Grade A

#63 - Sam Cooke's "Night Beat" (1963)

Night Beat is a nearly-perfect album that happens to be inside-out. I say "inside out," because it almost follows the arc of a live show, only in reverse. From the twelfth track to the first, Sam Cooke & company go from "late" to "later" to "last call" to "last chance" to "late for church." Beginning at the end with the bawdy barn-burner "Shake, Rattle & Roll," the whole band gets behind him on the chorus to raucous effect. And while it's definitely a strong song to close on, it would have worked even better as an opener, if only to get the sweat out of the crowd as the clock heads for the wee hours. From there, Sam and the boys could settle into the slow dances of "Fool's Paradise" and "Trouble Blues." Then, he could devastate the place with the minimalist blues of "Lost and Lookin'" (which may be the best song by Cooke you've never heard) and a return to his roots with the The Soul Stirrers on "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen." It is a traditional gospel song that he makes all the more classic with his plaintive rendering backed by a gently jangling guitar. What you don't hear on this album is almost as interesting as what you do. There is a profound lack of soloing. In fact, the instrumentation at all times - with the regrettable exception of "Little Red Rooster" - is complementary, but not conspicuous. Cooke takes full advantage of the space his band affords him, filling the cavernous studio with his rich, pure tones. Call it the "Well of Sound" approach. Even on "Laughin' and Clownin'," where he instructs his pianist to "tickle" the keys for him, he augments the moment with some playful vocal runs. Almost every available surface is lacquered in Cook's sweet, soulful voice. And with singing like that, why wouldn't they be? "Little Red Rooster" is a solid cut, to be sure. It's the only one that also appears on the excellent 31-track career retrospective Portrait of a Legend, 1951-1964. Here, though, it seems just the tiniest bit out of place. The band comes closer to the forefront and, at one point, the organ player even mimics the sounds of dogs a-barkin' and hounds a-howlin', like a rock 'n' roll version of "Livery Stable Blues." It belongs in the song only slightly more than actual canine accompaniment. Still, this is a minor misstep in an otherwise inspired set. Night Beat provides further proof to the amply-supported thesis that Sam Cooke knows soul, backwards and forwards. Grade: A

#62 - Ray Price's "Night Life" (1962)

Beware of introductions (including this one). Sure, they fill an organizational need, easing the reader into the reading. But, they are also a framing device, gently herding the audience into the head space where the writer wants them, to see things in a certain light. Ray Price's Night Life begins with an introduction and immediately my guard is up. I don't mind a well-scripted skit or other relevant atmosphere-building, but a direct monologue? That is suspicious. Price tells us that the set of songs was selected to reflect the emotions of those who do much of their living after hours. But do they? Some, like "The Twenty-Fourth Hour," fit this mold. Most of the others, however, are composed of the same, homogeneous heartbreak you'll find populating country songs around the clock. In the introduction, he specifically mentions "happiness" as one of the feelings he'll explore, but save the bouncing bass-lines on songs like "The Wild Side of Life" and "Sittin' and Thinkin'" (the latter's title being a euphemism for the type of introspection one does overnight in the county lockup), I'm hard pressed to remember hearing any "happy" moments. In fact, I'm hard pressed to remember any moments at all. This is a well-produced, well-performed collection of fairly bland music (with the possible exception of the Willie Nelson-penned title track), but as far as Price's claim that it "reflects" any aspect of real life, ante- or post-meridian, I'm afraid I have to call "bullshit" on that. I'm left with the impression that his introduction was a post-production patch job meant to help an ad hoc theme coalesce around these otherwise generic tunes. Personally, I think it backfired. Now the album seems to be more promise than payoff. Grade: C

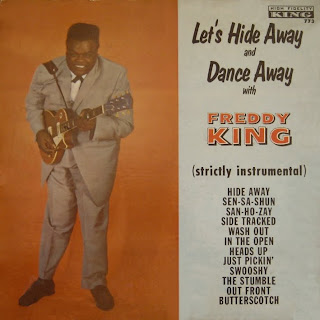

#61 - Freddie King's "Let's Hide Away and Dance Away with Freddy King" (1961)

C.S. Lewis, the professor, children's book author, and Christian apologist once wrote on the problem of pain. Our inability to understand it as a phenomenon, he said, stems from the limits on our perception. Feeling pain is primarily a sensory experience. How can you analyze what you feel as you feel it? Similarly, analyzing pain requires reason. And once you think about pain rationally, you are no longer feeling it in the moment. Similarly, Let's Hide Away and Dance Away with Freddy King is one of those albums that appeals mostly to two categories of listeners: dancers and guitarists. The dancers, as is their wont, couldn't care a hair what's going on musically so long as it moves them. And guitarists, looking to pick up a few tricks from a master, cease to consider the music from a purely emotional perspective. Of the three wise "Kings" of the electric blues (the others being Albert & B.B.), Freddie is the only one whose greatest hits were more often than not instrumentals. And, as this album's title implies, these are songs meant for soirees, ditties to dance to. Relegating King to the realm of "dance music," however, would overlook the impact he had on subsequent scores of guitarists, like Eric Clapton, who took his techniques and naturalistic sound to new heights. But while these later generations would employ complicated song structures to showcase their stuff, all King needs is a serviceable backbeat to help you shake a leg. The lead and best track "Hide Away" boasts a deceptively simple sound achieved by a series of rolling guitar licks that bend the notes, coaxing them into one another. This may not be flashy music, but neither is it hard to like. Grade: B

#60 - Joan Baez's "Joan Baez" (1960)

In the liner notes to Joan Baez in Concert, Part 2, there is a Bob Dylan poem in which he talks about how his notion of beauty was formed by singers like Hank Williams and "real" folk music only to be found in the ugly grit of the railroad lines, "in the cracks an' curbs / Clothed in robes a dust an' grime." As it continues, Dylan's ideas about beauty evolve and the poem ends up being the story of how his youthful rebellion was quelled, his anger cooled, his spirit softened, at least enough to allow him to listen to Baez and her three-octave range. Though the poem has always been one of my favorites, I had my doubts. Both of my parents love Joan Baez and so I grew up with an opportunity to get to know her, though I mostly squandered it. I found her voice a little too formal, a little too piercing, a little too pretty. So, I avoided her, unless she was singing duets with Dylan at his Philharmonic Hall concert in 1964 or with the Rolling Thunder Revue in the mid-70s. His gruff stuff is the washboard to her water and the songs all come out clean. On this, her debut album, her sonorous soprano is in peak form and she wields it with expert control. "El Preso Numero Nueve," the final track, is the most impressive. Not only is her Spanish gorgeous, but the tempo, too, robs her of the ability to hold those high notes too long, which can grate. In her defense, talent this rare can make it tempting to show-off even when it would be better to pull things back. These are, after all, simple songs, many of them sung to traditional airs with lyrics in the public domain. The same deadpan delivery that allows the singer to sing from another's perspective, regardless of race or gender (as Baez does on "Rake and Rambling Boy," among others), is an approach that allows the material to speak for itself. On the one hand, Baez's voice lent the heft of a vocal superstar to a music that was making a serious comeback and pushed the revival into overdrive. But did she outshine the songs she was attempting to introduce to a whole new generation? Bruce Eder, on AllMusic.com, in his review of the album, seems to confirm this criticism (though he considers it praise), when he refers to her singing as "so pure and beguiling that the mere act of listening to her - forget what she was singing - was a pleasure." As for me, I can't help but think that on this album, she steals the show, for better and worse. Grade: B-

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)