What the What?

Time

Well, as you can see, I'm way behind on my daily posts. A couple of weekends away from home and that's all it took to derail this train. Not abandoning this project; it's already introduced me to some great music and given me new directions to pursue. But I am going to put it on hold until I can give it the attention it deserves. Hopefully you've enjoyed what you've read. I've enjoyed what I've heard.

#64 - The Supremes' "Where Did Our Love Go?" (1964)

Applying the term "girl group" to The Supremes, though technically accurate, comes off dismissive when you're talking about the most successful American act of the 1960s. So many things had to go so right for this album to sound so good that lumping them in with all of the one-hit wonders and copycats is a disservice not only to the talent of Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard, but to the vision of Berry Gordy, the songwriting of composers like Smokey Robinson, and the priceless contributions of the woefully anonymous "Funk Brothers," Motown's in-house session band. While much media grist has been made of the internecine strife between the group's members, there is less than no evidence on these recordings of their inability to harmonize, literally or figuratively. In addition to the well known title track, "Baby Love," and "Come See About Me," the girls tear it up on Robinson's "A Breath Taking Guy," closing out the song by taking turns on the lead. And how about the uncredited guitar work on "I'm Giving You Your Freedom"? It starts out with just some simple plucking and gradually becomes more sophisticated as it bubbles up through the vocals. But no one outshines Ross, whose honey-dipped voice sets the tone for every single song. With singers like Tina Turner and Aretha Franklin about to come through the pop pipeline in the mid-60s, it's remarkable to hear a front-woman who opts for seductive restraint over unbridled power. Diana Ross & The Supremes make love, not war. Grade A

#63 - Sam Cooke's "Night Beat" (1963)

Night Beat is a nearly-perfect album that happens to be inside-out. I say "inside out," because it almost follows the arc of a live show, only in reverse. From the twelfth track to the first, Sam Cooke & company go from "late" to "later" to "last call" to "last chance" to "late for church." Beginning at the end with the bawdy barn-burner "Shake, Rattle & Roll," the whole band gets behind him on the chorus to raucous effect. And while it's definitely a strong song to close on, it would have worked even better as an opener, if only to get the sweat out of the crowd as the clock heads for the wee hours. From there, Sam and the boys could settle into the slow dances of "Fool's Paradise" and "Trouble Blues." Then, he could devastate the place with the minimalist blues of "Lost and Lookin'" (which may be the best song by Cooke you've never heard) and a return to his roots with the The Soul Stirrers on "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen." It is a traditional gospel song that he makes all the more classic with his plaintive rendering backed by a gently jangling guitar. What you don't hear on this album is almost as interesting as what you do. There is a profound lack of soloing. In fact, the instrumentation at all times - with the regrettable exception of "Little Red Rooster" - is complementary, but not conspicuous. Cooke takes full advantage of the space his band affords him, filling the cavernous studio with his rich, pure tones. Call it the "Well of Sound" approach. Even on "Laughin' and Clownin'," where he instructs his pianist to "tickle" the keys for him, he augments the moment with some playful vocal runs. Almost every available surface is lacquered in Cook's sweet, soulful voice. And with singing like that, why wouldn't they be? "Little Red Rooster" is a solid cut, to be sure. It's the only one that also appears on the excellent 31-track career retrospective Portrait of a Legend, 1951-1964. Here, though, it seems just the tiniest bit out of place. The band comes closer to the forefront and, at one point, the organ player even mimics the sounds of dogs a-barkin' and hounds a-howlin', like a rock 'n' roll version of "Livery Stable Blues." It belongs in the song only slightly more than actual canine accompaniment. Still, this is a minor misstep in an otherwise inspired set. Night Beat provides further proof to the amply-supported thesis that Sam Cooke knows soul, backwards and forwards. Grade: A

#62 - Ray Price's "Night Life" (1962)

Beware of introductions (including this one). Sure, they fill an organizational need, easing the reader into the reading. But, they are also a framing device, gently herding the audience into the head space where the writer wants them, to see things in a certain light. Ray Price's Night Life begins with an introduction and immediately my guard is up. I don't mind a well-scripted skit or other relevant atmosphere-building, but a direct monologue? That is suspicious. Price tells us that the set of songs was selected to reflect the emotions of those who do much of their living after hours. But do they? Some, like "The Twenty-Fourth Hour," fit this mold. Most of the others, however, are composed of the same, homogeneous heartbreak you'll find populating country songs around the clock. In the introduction, he specifically mentions "happiness" as one of the feelings he'll explore, but save the bouncing bass-lines on songs like "The Wild Side of Life" and "Sittin' and Thinkin'" (the latter's title being a euphemism for the type of introspection one does overnight in the county lockup), I'm hard pressed to remember hearing any "happy" moments. In fact, I'm hard pressed to remember any moments at all. This is a well-produced, well-performed collection of fairly bland music (with the possible exception of the Willie Nelson-penned title track), but as far as Price's claim that it "reflects" any aspect of real life, ante- or post-meridian, I'm afraid I have to call "bullshit" on that. I'm left with the impression that his introduction was a post-production patch job meant to help an ad hoc theme coalesce around these otherwise generic tunes. Personally, I think it backfired. Now the album seems to be more promise than payoff. Grade: C

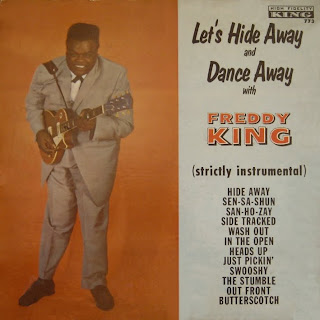

#61 - Freddie King's "Let's Hide Away and Dance Away with Freddy King" (1961)

C.S. Lewis, the professor, children's book author, and Christian apologist once wrote on the problem of pain. Our inability to understand it as a phenomenon, he said, stems from the limits on our perception. Feeling pain is primarily a sensory experience. How can you analyze what you feel as you feel it? Similarly, analyzing pain requires reason. And once you think about pain rationally, you are no longer feeling it in the moment. Similarly, Let's Hide Away and Dance Away with Freddy King is one of those albums that appeals mostly to two categories of listeners: dancers and guitarists. The dancers, as is their wont, couldn't care a hair what's going on musically so long as it moves them. And guitarists, looking to pick up a few tricks from a master, cease to consider the music from a purely emotional perspective. Of the three wise "Kings" of the electric blues (the others being Albert & B.B.), Freddie is the only one whose greatest hits were more often than not instrumentals. And, as this album's title implies, these are songs meant for soirees, ditties to dance to. Relegating King to the realm of "dance music," however, would overlook the impact he had on subsequent scores of guitarists, like Eric Clapton, who took his techniques and naturalistic sound to new heights. But while these later generations would employ complicated song structures to showcase their stuff, all King needs is a serviceable backbeat to help you shake a leg. The lead and best track "Hide Away" boasts a deceptively simple sound achieved by a series of rolling guitar licks that bend the notes, coaxing them into one another. This may not be flashy music, but neither is it hard to like. Grade: B

#60 - Joan Baez's "Joan Baez" (1960)

In the liner notes to Joan Baez in Concert, Part 2, there is a Bob Dylan poem in which he talks about how his notion of beauty was formed by singers like Hank Williams and "real" folk music only to be found in the ugly grit of the railroad lines, "in the cracks an' curbs / Clothed in robes a dust an' grime." As it continues, Dylan's ideas about beauty evolve and the poem ends up being the story of how his youthful rebellion was quelled, his anger cooled, his spirit softened, at least enough to allow him to listen to Baez and her three-octave range. Though the poem has always been one of my favorites, I had my doubts. Both of my parents love Joan Baez and so I grew up with an opportunity to get to know her, though I mostly squandered it. I found her voice a little too formal, a little too piercing, a little too pretty. So, I avoided her, unless she was singing duets with Dylan at his Philharmonic Hall concert in 1964 or with the Rolling Thunder Revue in the mid-70s. His gruff stuff is the washboard to her water and the songs all come out clean. On this, her debut album, her sonorous soprano is in peak form and she wields it with expert control. "El Preso Numero Nueve," the final track, is the most impressive. Not only is her Spanish gorgeous, but the tempo, too, robs her of the ability to hold those high notes too long, which can grate. In her defense, talent this rare can make it tempting to show-off even when it would be better to pull things back. These are, after all, simple songs, many of them sung to traditional airs with lyrics in the public domain. The same deadpan delivery that allows the singer to sing from another's perspective, regardless of race or gender (as Baez does on "Rake and Rambling Boy," among others), is an approach that allows the material to speak for itself. On the one hand, Baez's voice lent the heft of a vocal superstar to a music that was making a serious comeback and pushed the revival into overdrive. But did she outshine the songs she was attempting to introduce to a whole new generation? Bruce Eder, on AllMusic.com, in his review of the album, seems to confirm this criticism (though he considers it praise), when he refers to her singing as "so pure and beguiling that the mere act of listening to her - forget what she was singing - was a pleasure." As for me, I can't help but think that on this album, she steals the show, for better and worse. Grade: B-

#59 - Frank Sinatra's "Come Dance with Me!" (1959)

Not one, but two of the singles from Jay-Z's The Blueprint 3 catch the most successful hip-hop artist in history comparing himself to Frank Sinatra. This is not a coincidence. For most of its relatively short history, rap has prided itself on its neophilia. Always "on to the next one," no music fans chew 'em up and spit 'em out quite like rap fanatics. Prior to Jay-Z, you were less likely to see a 35-year-old rapper - much less one still selling albums - than a 35-year-old MVP in the NBA. So in the most self-referential of American musical genres, the one in which those writing lyrics are constantly crafting superlatives to set themselves apart from the crowd, Jay-Z is in a class all his own. It's really not up for debate. His unprecedented tenure on the hip-hop throne has made it futile for him to compare himself with others in the field. In fact, it's become so obvious to him that he now consciously looks to the past for his peers. As he rightly observed in "What More Can I Say?" on 2003's The Black Album, "There's never been a n**** this good for this long / this hood or this pop, this hot or this strong." So, why Sinatra? Why not The Beatles or Elvis Presley? Well, truth be told, he has drawn parallels to them as well. But, The Beatles were a group, not to mention British. And "the King," despite sharing the record for number one albums with Jay-Z until recently, has always been a slightly awkward match due to the tenuous relationship between the singer and the African-American community, segments of which have directed rancor toward Presley since an apocryphal rumor alleging he'd made racist remarks began circulating in the 1950s. Still, it wasn't mere process of elimination that nudged Jay-Z to gravitate towards Sinatra. No, the former CEO of Def Jam Recordings shares some actual common ground with the Chairman of the Board. Both have the New York connection (Sinatra from Hoboken, NJ, Shawn Carter from Brooklyn), both act as the epicenter of informal entertainment syndicates (the Rat Pack; Roc-A-Fella affiliates), but, most importantly, both count swagger - that all-encompassing commodity of confidence - among their prime assets. On Come Dance With Me!, one of the many theme albums Sinatra cut for Capitol and then his own label, Reprise Records, the singer takes an activity most tough guys consider uncool and uses his Midas touch to turn it into trend-setting gold. Billy May's big band arrangements are robust, but there's no question who's really in charge. Die-hard supporters might disagree, but Sinatra's voice has some conspicuous flaws. His gift is to make the listener forget all about these limitations as he treats these tunes like his playthings. There is a raw magnetism in his vocal personality that makes all of the tracks here sound natural and unforced. What many who followed in his footsteps (with the exception of Jay-Z) have failed to realize is that being "cool" isn't about not caring. It's about never letting them see you sweat, as if it all comes easily to you. Grade: A-

#58 - Billie Holiday's "Lady in Satin" (1958)

I am fascinated by the beauty of decay. On four separate occasions I was privileged to visit a college professor of mine at her summer home in Belturbet, Ireland. It is a country house on a working dairy farm with all the dust, dung, and cobwebs you could want in such a rustic setting. Sometimes it feels like the earth is slowly reclaiming the whole structure as the trees and creeping vines seem as if they are playing a long game with an eye to devouring it. But each year it presses on, an eventual ruin, in all its spectacular and decrepit glory. When it comes to music, I have an epicurean taste for the various stages of Bob Dylan's vocals, as they, too, have lapsed into irredeemable disrepair. Much of the music he has produced in the twilight of his career has a timeless quality that is well-complemented by his ancient-sounding rasp. "Not Dark Yet," "High Water (for Charley Patton)," and "Nettie Moore" from three of his most recent studio albums are exemplary specimens all. Sadly, with his most recent album, Together Through Life, those spooky vocal cords of his finally gave up the ghost. Johnny Cash, too, experienced a late-period revival and managed to get much of his physical decline committed to tape throughout all those Rick Rubin-helmed LPs for the American Recordings imprint. At their best, his performances on those albums are hypnotic. In many cases it is the eerie, wizened sound of a man singing about death as if he's already met his own. What makes Dylan and Cash successful, of course, is the perfect pairing of sound with subject. Who can better bellow "We'll Meet Again" than the man for whom the afterlife is closer than that distant shore? Now, the consummate singer can adapt any song to her style or adapt her style to any song. In her prime, this was certainly the case with Billie Holiday. On Lady in Satin, she is not in her prime. Recorded about a year and a half before she died, much of her range is gone and there is an audible strain when she tries for the higher and lower notes. Her voice does invest these torch songs with an emotional vulnerability that is fitting for many of the lyrics, but not all of them. Again, it's all about how well you marry what you're singing with how you're singing it. The trick with these lover's laments is to sound wounded, but not defeated. Unfortunately, after being ransacked by decades of disease and drug abuse, Holiday was out of tricks. Grade: C

#57 - Pete Seeger's "American Industrial Ballads" (1957)

There is something inherently valuable in the material released by the Smithsonian Folkways label that goes well beyond its artistic merit. Scholars like John & Alan Lomax, Harry Smith, and Moses Asch who recorded and compiled folk songs conceived of their work as musical appreciation, yes, but also as cultural preservation. It is this preservationist attitude that informs the selections and performances on Pete Seeger's American Industrial Ballads. A protégé of Woody Guthrie's, Seeger has lived his whole life steeped in the songs and stories passed down by generations of Americans. Consequently, his knowledge of the folk milieu in which he performs is every bit as encyclopedic as the archivists who document it. Over the course of 24 tracks, Seeger takes listeners on a tour of coal mines, cotton mills, picket lines, homesteads, rail yards, and the shabby dwellings of the underpaid and overworked. Lively characters inhabit these places; some are the tragicomic protagonists of hard-luck ballads and some are the feisty wiseacres damning the man and calling their comrades to arms. Long-gone lingo like "doffers," "bobbins," and "blacklegs" hearken back to a way of life that has since faded into the past, even as archaic songs like "Peg and Awl" presage further mechanization and the Luddite conflicts to come. You'll also hear plenty of black humor and hearty insights, like on "Hard Times in the Mill" when the narrator sardonically relates his morning routine: "Every morning, half-past five / gotta get up, dead or alive." And as much as these songs function as a receptacle of history - a time capsule for this priceless and poetic idiom - they are also a refuge for the workers who sang them and whose lives are sung in them. Seeger approaches the project with an earnestness that is both touching and catching. But his sincere reverence for the music borders on staid politeness. What he does resembles a studied act of anthropology more than it does a guitar pull or hoe-down. Had he truly wanted to resurrect the spirit and not just the letter of these tunes, he might have performed them in one of the union halls he loved so well. Grade: B-

#56 - Elvis Presley's "Elvis Presley" (1956)

The following is an excerpt from an early draft of Cameron Crowe's screenplay for Almost Famous:

Ext. Downtown San Diego Radio Station - DayGrade: A

A slovenly, hyperkinetic man is darting from shelf to shelf, dishing out quick and gutting reviews of the station's record library. This is the legendary critic, Lester Bangs. Expounding on the greatness of The Guess Who and Iggy Pop, he delivers a brief, erratic soliloquy on the mystical origins of rock 'n' roll.

"Here's a theory for you to disregard...completely. Music, you know - true music - not just rock 'n' roll - it chooses you. It lives in your car, or alone, listening to your headphones - you know, with the vast, scenic bridges and angelic choirs in your brain. It's a place apart...from the vast, benign...lap of America. Take Elvis. Elvis Presley! You think that man ripped off Little Richard? No! He was an emissary, the go-between, a numbers runner. You know, here he is, this young, truck-driving whelp, out of Tupelo-thank-you-ma'am-backwater-Mississippi - young and hungry, mind you - and he's living, I mean living, at these black clubs in Memphis, man. Soaking it up... and on the radio, too. Hell, the south was so segregated you weren't supposed to listen to a black station. And that's what nobody gets - people think it was T.V. - that T.V. made the music. Well, T.V. might have been the midwife, but it was radio knocked the country up. Got everyone nice and cozy at the petting party. All those waves in the night, just towers knocking down walls...Elvis was a Branch Rickey. And Jackie, yeah, Jackie in that Brooklyn blue, he had the talent, but Branch Rickey saw the window and jumped. Just listen - listen to that first album, those Sun sides, man, and it's there...no more Amos 'n' Andy, they were gone with the wind, because the kids were on board and the PTA couldn't say 'no' - not for long - not to a clean-cut army boy no matter which way his hips flipped..."

#55 - Hank Williams' "Hank Williams as Luke the Drifter" (1955)

The alter-ego is a mainstay of pop music. Some performers adopt them for a single album (Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Chris Gaines, Sasha Fierce). Others use them in concert to articulate a skewed perspective, (the Night Tripper), more closely resemble the subjects of their songs (Boxcar Willie), or to

assume a different frame of mind (the Man in Black, the Fly/MacPhisto). Occasionally, the arrival of a novel persona can signify a foray into new musical territory (Ziggy Stardust) or the exorcism of the baser elements in one's soul (Slim Shady, T.I.P., Roman Zolansky). With "Luke the Drifter," Hank Williams sought to cultivate a space in which he could touch upon some of the more devoutly Christian strains in his thought. Already a superstar by the mid-1950s, it was important for him to insulate the success he'd had with his winning formula of secular songs about honky-tonkin' and heartbreak. And musically this album is as much a departure for Williams as its thematic content. The vast majority of these tracks feature the Drifter waxing philosophic about all manner of vice in a salt-of-the-earth spoken word, with only the occasional singing. His cowboy cadence mostly follows a simple A-B-A-B scheme, but some of the rhymes are downright amazing. Williams scores major points, for instance, in "The Funeral," when he says "rose a sad, old colored preacher / from his little wooden desk / with a manner sort of awkward / and a countenance grotesque." Unfortunately, he loses all of these points elsewhere in the song when he refers to the minister's "Ethiopian face" and the "curly hair" and "protruding lips" of the child he's eulogizing. There are several moments like these that might make the modern ear recoil, but some would be shaky in any age. Consider "Be Careful of the Stones That You Throw," Williams' rebuke of hypocrisy. A woman comes to gossip about a young female neighbor and her hard-partying ways (which our dear departed singer certainly knew something about). But, lo and behold, when that same woman's child is later saved from an oncoming car, guess who it was came to the rescue? Unfortunately, the muddled moral doesn't quite fit with the rest of the story. The chorus would have us guard against finding fault in others, but the conclusion seems to suggest there is both good and bad in everyone. "Please Make Up Your Mind" is a song sung by a man dealing with his fickle woman. Somehow it seems unfair to lump her faults in with the others. And I'm really not sure what's going on with "Everything's Okay," where a farmer, condemned to Job-level misfortune, keeps insisting that just being alive makes everything hunky-dory. Of all the songs, "Just Waitin'" is the best, boasting a trove of wry observations about how life works, but even it's not enough to right the rest of this album's wrongs. Moralizing like this would be a little hard to take in the best of circumstances, but from an unrepentant scoundrel like Hank Williams it'd be downright intolerable. Good thing Luke the Drifter does the talking. Grade: D

#54 - Louis Armstrong & His All Stars' "Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy" (1954)

"I have made an important discovery," Oscar Wilde is said to have mused, "...alcohol, taken in sufficient quantities, produces all the effects of intoxication." This has always been my favorite quote from that eminently quotable Victorian. For starters, it's not funny. Not by itself. The statement's humor is utterly contingent on the personality of its author. Spoken by almost anyone else (except maybe Winston Churchill) it becomes a banal and uptight truism. But, because you're expecting Wilde to say the perfect thing - the kind of thing you always wish you'd have said in the moment as opposed to thinking up on the ride home from wherever - it is made profound by virtue of its non-profundity. That is the power of reputation. It can imbue its owner with special properties and coax goodwill from an audience ready to meet him more than halfway. My only personal experience of this type of charisma came in 2001, when I had the good fortune to see a taping of Late Night with Conan O'Brien. After waiting in various hallways for the hours before the show began, we were all primed to receive the man we'd come to see. When he finally made his entrance, we laughed at everything he did. Everything. We were putty in his hands. Similarly, even before pressing "play" on my iPod, I feel as if liking Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy was almost predetermined. This is an album featuring one legend performing the songs of another. Louis Armstrong, the ambassador of jazz, and W.C. Handy, a composer who helped legitimize the blues. With the help of a crack ensemble (the All Stars) - and especially the vocals of Velma Middleton - Armstrong shows what world-class musicians can do when they have material worthy of their talents. The interplay between the instruments is exciting and though Satchmo's trumpet leads the way, everyone is given a chance to shine. The frisky back-and-forth between Middleton and Armstrong (who is full of mischief here) as they trade barbs, flirtations, wisecracks, and punchlines is a wonderful showcase for the joyous humor that this music stirs up in people. Many of the song titles highlight the various locales from which the blues hail: "St. Louis Blues," "Long Gone (from Bowling Green)," "The Memphis Blues (Or Mister Krump)," "Beale Street Blues," Ole Miss Blues," "Atlanta Blues (Make Me One Pallet On Your Floor)," and - via Armstrong's own New Orleans - "Chantez La Bas (Sing 'Em Low)." You really couldn't ask for better tour guides. Like Wilde, Armstrong's reputation is not only well-earned, but it was well-honed. Scholars insist that many of the witticisms attributed to Wilde were likely developed through hours of preening. Only by primping himself in private was he able to summon the charm he commanded in public. So, too, Armstrong's music has an improvisational feel, though by 1954 he had been playing for so long that for him spontaneity was second nature. As a listener, I'm not certain whether the group's genius lies in making well-rehearsed moments sound so loose or in making organic music in such an expert fashion, but I am certain it doesn't matter. Grade: A+

Subjects:

1950s,

Grade "A+",

jazz,

Louis Armstrong,

W.C. Handy

#53 - Beck's "Sea Change" (2002)

Like fellow genre-hoppers David Bowie and Prince, it isn't always clear where Beck's soul calls home. Is he a mad dabbler, the jack of all trades and master of none? Or is he a genuine polymath with no clear allegiances to any specific style or substance? Such questions make it easy to commit one of two errors when listening to Sea Change. The first would be to consider it a one-off, with no more of the man himself in it than he put into the tongue-in-cheek lounge sleaze of Midnite Vultures' "Debra." But, if this album only means to send up or approximate sadness rather than convey the real thing, then Beck needs to quit his day job and start acting full-time. The second misstep would be to think of Sea Change as a skeleton key to the one true Beck, a portal offering a fleeting glimpse into his psyche. The latter path is probably the more perilous considering how many critics who thought Blood on the Tracks was the best breakup album of all time were stunned when Bob Dylan claimed the songs were instead based on the short stories of Anton Chekhov. To me, more compelling than debates about the album's literal truth is the question of how its sound came to be. Nigel Godrich's production is lush and soft, almost like it belongs on 70s AM radio. Beck's voice is forlorn, even on tracks like "Sunday Sun" that hint at memories (or premonitions) of a life less hard. To sustain this type of minor-chord melancholy without becoming morose requires a whole lot of talent and even more discretion. Most remarkable, perhaps, is the extent to which the music is unclassifiable yet wholly "Beck," while still employing familiar structures and hinting at clear influences. Just as there's something very punk rock about the three-chord strum and in-your-face morality of Woody Guthrie, so too is Sea Change a country album in spirit, if not sound. One obvious historical touchstone for this type of full commitment would be The Velvet Underground's Loaded, which found Lou Reed creating polished pop rock mostly just to prove he could be commercially appealing if he really wanted to be. With songs as strong as "The Golden Age," "Lost Cause," and "Lonesome Tears," the burden of proof has to be on this album's detractors. If "country-tinged balladeer" is just one of the many hats Beck can wear, then it's an awfully good fit. Grade: A

#52 - Little Richard's "Here's Little Richard" (1957)

Like other singers of his stripe, Little Richard is in desperate need of some historical revision. For a variety of reasons, the earliest generation of rock 'n' rollers were cut down in their prime as if they were cursed. Whether it was scandal (Jerry Lee Lewis), drugs (Johnny Cash), legal trouble (Chuck Berry), accidents (Carl Perkins) or military service (Elvis Presley), all of these young men ran afoul of fate. "Little Richard" Penniman opted out of touring for a healthier reason - he got religion - but the havoc it wreaked on his recording career was much the same as that which ravaged his peers. Of course there's nothing to be done about decisions made in the past, but curating one's legacy is another matter altogether. Lewis generated some buzz with last year's Mean Old Man. Cash, through a curious combination of stark honesty in his autobiography and the Hollywood romanticism of Walk the Line, has cemented his place in the musical firmament. Berry's still plugging away once or twice a month in the Duck Room at Blueberry Hill, but has yet to receive the accolades, acclaim, or accounting treatments commensurate with his genius. Perkins has profited from a renewed interest in the Million Dollar Quartet, but will likely continue to be overshadowed by his more famous counterparts. And Elvis, well, his fame is great and growing. If you believe musicians' memoirs, Little Richard was the reason for more high school talent show entrants, rowdy garage bands, piano lessons and guitar sales than any of his contemporaries. Listening to Here's Little Richard, it's not hard to see why. This is youth-oriented party music. Over the course of twelve tracks he doesn't exhibit many different moods, but then who wants to be maudlin while dancing? The vocals throughout are gleeful and raspy, finding Little Richard's voice in various states of frantic disrepair (likely having sung his lungs out the night before). And if his singing is expressive and exclamatory on songs like "Tutti Frutti" and "Rip It Up" then his piano work is downright explosive on "Slippin' and Slidin'" and "Long Tall Sally." Those keys wait for no man. For the closer, "She's Got It," he delivers the lyrics so fast, it almost sounds like Ray Charles on a broken record player. If there's any real criticism to be found, it's either that the scattered recording sessions yielded varying degrees of sound quality or else the years have been kinder to some masters than they have to others. It might also be possible to say that Little Richard isn't well-rounded, that his music lacks nuance. Well, if he's a one-trick pony, then it's worth remembering that this is a pretty damn good trick. Grade: B+

#51 - Jeff Buckley's "Grace" (1994)

Drunk or not, swimming in the Mississippi with clothes on was a stupid move. And not just because it's a physical feat that would bedevil a seasoned swimmer. No, it was stupid because it was a waste of real, raw talent. In fact, it was as stupid as Grace is brilliant. Jeff Buckley's debut album is an eclectic masterpiece that showcases mind-boggling versatility, restless creativity, and a voice that should've been on the federally protected species list. It positively sprawls. And not in the sense of The Suburbs, where "sprawling" means the purposeful march to annex more of the same. There's nothing quite so systematic here. Rather, at turns, this album fitfully and listlessly spreads out a wide open musical landscape and then settles it with unsettling valleys, peaks, and plains. On the title track, it lopes. On "Lilac Wine," it drapes. On "Mojo Pin," it lingers (and malingers). Buckley wails and croons, moans and cajoles. And like any good Renaissance man, he does all of them well. His range is dizzying. "Lover You Should've Come Over" is about as romantic as songs can get (even if it likely launched a thousand John Mayers). It being 1994, a few of the tracks are weighed down by a leaden grungy crunch, but most of the arrangements are tasteful and invigorating. Particularly, the cover of Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" - a song that seems to have been sung more than "Happy Birthday" - is a perfect compromise between restraint and exultation. It begins with Buckley letting out a weary, sighing exhalation and then, over the tones of a lone chiming guitar, he moves between sweet, whispered lows and heart-breaking, hollered highs. Here and elsewhere ("Corpus Christi Carol") he exhibits a gift for sometimes formal, sometimes jazzy enunciation that calls to mind his famous father or more modern singers like Antony. The riverboat hustlers of the Mississippi probably robbed millions of dollars from rubes and dupes over the years, but those crimes are petty next to what Big Muddy stole from music when Jeff Buckley waded in for that fateful midnight swim. Grade: A-

#50 - Deep Purple's "Machine Head" (1972)

If there are rules to reviewing, the cardinal of these must be: "don't criticize something for not being what you'd prefer it to be; judge it on its own terms." Not only is it the only honest way to go about comparing apples and oranges, it also mitigates against the biases we all carry with us. Simply put, if you're listening to a rock album from the 1950s and you think that what it's really missing is extended organ solos, then maybe you're not being a fair arbiter. And while it might not be realistic to believe you have the imagination to put yourself in the time and place when and where your subject was produced, you nonetheless have to try. Machine Head is one of the marker stones for the journey that blues-inflected rock 'n' roll took on its way to heavy metal. On a purely historical level, Deep Purple is an utterly fascinating outfit. They are pioneering architects of sound. The music on this album, however, is of inconsistent quality. "Highway Star" explodes out of the gate with almost as much insistence as "Black Dog." From there, the band dials it back on "Maybe I'm a Leo." Maybe too much. I understand not wanting to blow your wad all at once, but for an album that comes in at a little over 37 minutes, you really don't have any room for weak tracks and this snoozer looks back to Led Zeppelin more than it looks ahead to anything fresh. "Pictures of Home" starts to turn things around before "Never Before" pulls the full 180. It is likely the best song on the album with its slow, funky start giving way to some seriously hard-rocking verses and a killer bridge melody that would make Alex Chilton proud. Then comes the radio staple "Smoke on the Water," with its autobiographical lyrics detailing the band's trials and tribulations in Montreaux. Unfortunately, the song's ubiquity tends to work against it here. In 1972, the listener would have likely considered it the high point, a centerpiece. Now its omnipresence surrounds it with a "been-there-done-that" aura rendering a once-powerful song tepid and tired. The penultimate "Lazy" is anything but as most of the band's experimentalism is consolidated within its seven-minute span, but album closer "Space Truckin'" does seem a little half-assed. The song is a disappointment if only because its music & words forge an uneasy truce between bleating R&B and semi-serious sci-fi. It is no less dignified than Robert Plant's Tolkien-inspired flights of lyrical fancy, but somehow sillier because it comes off as a half-measure. Had Ian Gillan gone all in with the theme - instead of occupying a kind of fatuous middle distance between ramblin' blues rumble and Lost in Space-level lyrics - it might have been far more successful. Plenty of prog-rock bands at that time were exploring the outer reaches of the universe, so it doesn't strike me as unreasonable to take Deep Purple to task for goofing about. Think about it: when you're in China, eating the local cuisine, you no longer call it "Chinese food." And when you're a real space trucker, you'd probably drop the adjectival qualifier on that phrase, too, wouldn't you? Grade: B

#49 - Cat Stevens' "Tea for the Tillerman" (1970)

In one sense, Cat Stevens has always been a man between worlds. He was born Swedish and Greek. Raised in England. Wrote popular songs for money and then introspective, self-consciously "folk" songs for even more money. Abandoned his fame, converted to Islam, and then retired from music, resurfacing every so often to generate controversy and sue those he alleged were copying his songs. Absent the other details, the "celebrity-turned-recluse" story is only slightly less common than the against-all-odds rise from obscurity to popularity. Tea for the Tillerman marks Stevens' breakthrough as a recording artist. It (along with its 1971 follow-up, Teaser and the Firecat), contains his best-loved songs from his period of greatest creative fecundity. So...why is it so annoying? Well, for starters, Tillerman finds Stevens walking the fine line between sentiment and schmaltz and often erring on the side of the latter. "Where Do the Children Play?" asks the opener, a question lamenting the dubious advances of the modern age - a perspective, incidentally, to which I might otherwise be sympathetic - but which is posed in such a laughably earnest fashion, you realize why the name "Cat Stevens" has become a coded punchline for authors like Nick Hornby. From there, unbelievably, things get worse, then better, and finally end. "Wild World" establishes a new watermark for creepy break-up songs as Stevens sings to the girl leaving him, "I'll always remember you like a child, girl." "Miles From Nowhere" is interesting at first until you realize the lyrics only appear to make sense. Being "miles from nowhere" literally means being somewhere, but that's not how Stevens uses it. So, like the phrases "I could care less" or "each day worse than the next," it's nonsense. On "Longer Boats," Stevens scoops Bill "You Can't Explain That" O'Reilly by four decades, insisting "nobody knows / how a flower grows." Yeah, nobody. Except botanists! This is the kind of driveling palaver that gives hippies a bad name. "Father and Son," unlike the other songs here, is genuinely affecting (as opposed to affected), but - tellingly - it is the only track for which co-songwriting credit is given. In 2003, Stevens won a plagiarism lawsuit against the The Flaming Lips, for co-opting part of its melody for "Fight Test." You will notice however that neither they nor any of the other groups sued by Stevens were ever accused of ripping off his lyrics. Grade: C-

#48 - Ike & Tina Turner's "River Deep ~ Mountain High" (1966)

If half the stories about Phil Spector are true, then he is a mad genius on the order of Drs. Frankenstein and Jekyll. But whereas most people focus on the monstrosity of their creations, we shouldn't forget that all three, as scientists, were also visionaries. Whether you're dallying in corpse reanimation, striving to unleash the human beast, or toiling away at a towering Wall of Sound, you will meet your fair share of naysayers. By 1966, the public's fickle tastes had veered far away from the early- to mid-60s smashes of "Be My Baby" and "Then He Kissed Me." Suddenly there seemed to be no room at the inn for the meticulous, orchestral pop Spector had made so famous, no room unless your album was called Pet Sounds or Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. By any reasonable artistic standard, River Deep - Mountain High is amazing. Tina Turner's singing throughout is a thing of raggedly majestic beauty. On the title track, you can actually hear the toll that Spector's fastidious obsession has taken on her voice and it still manages to transcend his dense, overwhelming production. Stylistically, Turner is unstoppable. She goes blow for blow with the blues on "I Idolize You," matches the sound of a late-night soul throw-down on "A Fool in Love," and injects some R&B power into the pop of "A Love Like Yours (Don't Come Knocking Everyday)" and "Save the Last Dance." If Ike Tuner was integral as a sessions musician or as the bandleader for their stage show, you couldn't tell that from this. He does kick in some nice bass vocals on "Make 'Em Wait," but his contributions to "It's Gonna Work Out Fine," the album's closer - and only clunker - are embarrassingly bad. It's an artless, egotistical intrusion - like when Diddy used to do that pointless cheerleading over a Biggie Smalls track. This is a nearly perfect album, showcasing Turner in her prime and Spector at the height of his game. It's...aliiiive! Grade: A

Subjects:

1960s,

Grade "A",

Ike and Tina Turner,

Phil Spector,

pop,

soul

#47 - Emmylou Harris' "Elite Hotel" (1975)

Those well-versed in epistemology probably have a name for the phenomenon, but surely you've experienced it yourself. That funny blind spot that obscures a word or a concept prior to your learning what it means. But, because you can't miss something you've never had, you really only become cognizant of having missed it after you've been formally introduced. Suddenly, it's everywhere, hiding in plain sight, and you wonder how you never noticed it before. A funny (and similar) thing happened to me on the way to getting to know Emmylou Harris. There I was, listening to Desire, hearing Bob Dylan sing "One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below)" and "Oh, Sister" with some mysterious, silver-throated chantreusse and loving every minute of it. A year later I heard Gram Parsons sing "We'll Sweep Out the Ashes in the Morning" and only then made the connection that the two women were the same woman and that woman was Harris. It began to seem as if you couldn't turn on the music of any red-blooded, country-loving boy without hearing him duet with Emmylou (or someone who was trying powerful hard to sound like her). The Band had her stand in for "Evangeline," a studio-cut add-on to The Last Waltz, while Bright Eyes put her gifts to good use I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning. More recently, Mark Knopfler employed her help to produce the unconscionably gorgeous All the Roadrunning, a collaboration seven years in the making. Naturally, as a cursory glance at her guest appearance credits will tell you, these examples are a handful of sand on the beach of her accomplishments. But what about her and her alone? Is she a glorified sideman? A supporting actress? An anonymous and faceless hired gun called in to save the poor, beset-upon Mexican village, requiring no payment for the chivalrous deed? Maybe. But just because she's a generous spirit doesn't mean she lacks the chops to strike out on her own, as she does here on her debut. First off, she's got personality to spare. Listen as she torches her way through "Feelin' Single - Seein' Double" and "Ooh Las Vegas." You show me a female country singer who flashes more raw talent or honky-tonkin' confidence than her and I'll show you Waylon Jennings in drag. Of course, faster numbers like these were the biggest revelation for me because God knows she can sing a ballad. The only strange moment comes during her cover of The Flying Burrito Brothers' "Sin City." On the original, Parsons & Chris Hillman lend their voices to an ethereal two-part harmony, but here Harris - backed up by Rodney Crowell & Linda Ronstadt - adopts a weird, third-way melody that, while beautiful, gestures toward the absence of the original Grievous Angel. In terms of arrangements, it's analogous to setting a place at the table for someone who's passed on, as Harris pays tribute to her fallen mentor and friend, Parsons, who died of an overdose in '73. It's a moving version of the song, but it also underscores that she will likely always be better known for the ways in which she enhanced other people's music than her own. But, before you're tempted to offer any bullshit, "behind-every-man" platitudes, know that if Harris is pop music's ultimate team player, then it's by design. One listen to Elite Hotel and you'll be convinced that the only person standing in the way of her becoming a superstar in her own right is herself. To be or to be collectively, that is the question. Either way, Emmylou Harris - as a solo artist and as a collaborator - is her own fiercest competition. Grade: A-

#46 - Elliott Smith's "Either/Or" (1997)

I love Bill Bryson. Whether writing about the Appalachian Trail, the English language, or the sum total of our scientific discoveries to date, he has a real flare for making dry topics exciting. More accurately, he specializes in framing a subject in such a manner as to make that which is most exciting in it reveal itself. I also like his modesty as an author. He knows when he's licked. If there is content - like quantum theory or the boredom of arduous hiking - that by its very nature is either too vague or too tedious to be compelling, he doesn't force it. Rather, the writing becomes a meditation on the difficulty of describing the indescribable or the nondescript. And, because he's intelligent and funny, this works in a pinch to draw the reader back in. I wish Bryson could ghost-write this review of Elliott Smith's Either/Or because I can't for the life of me find a single interesting thing to say about it. It's not that it's bad exactly. "Bad" can still provoke a response. This is just bland, boring, by-the-numbers indie rock. What Jack Black's character from High Fidelity might call "sad bastard music." On the song "Rose Parade," when Smith sings, "They say it's a sight that's quite worth seeing / It's just that everyone's interest is stronger than mine / When they clean the streets, I'll be the only shit that's left behind," all I can think is "Oh, somebody just give this guy a hug and get him to shut the fuck up already." Of course, Bill Bryson would've put it in a much wittier way. I know Bill Bryson. Bill Bryson is a fave of mine. I am no Bill Bryson. Grade: C-

Subjects:

1990s,

Elliott Smith,

Grade "C-",

indie,

rock

#45 - T.I.'s "King" (2006)

Back in 2003, Michael Caine was on a press junket publicizing his then-current project, Secondhand Lions. In the movie, he and Robert Duvall are a pair of geriatric action heroes living in Texas, when they are forced to play nursemaid to their 14-year-old nephew (Haley Joel Osment). In an interview on Late Night with Conan O'Brien, the very British Caine explained how his accent coach helped him achieve his character's impressive Lone Star lilt. He said that the King's English has a stiff, upright pronunciation. Think of someone with good posture in a heavily starched shirt. The Texan, on the other hand, 'llows his words to lay down on top o' one 'nother like they're jes settin' a spell. Caine's demonstration provided not only entertainment, but also some homespun wisdom about the intricacies of regional dialect patterns. Certainly there is something inherently musical about southern speech, with its prolonged drawl and lazy cadences. Indeed, nowhere is the hip-hop concept of "flow" used quite so instructively as when describing southern rap. Pharrell once described T.I. as the "Jay-Z of the south," but listening to King, I admit I didn't quite see the connection at first blush. Then it dawned on me that while the two artists share a background in drug dealing, what really unites them is delivery. One of Jay-Z's strengths - among many - is his otherworldly ability to rhyme words that on paper have no business rhyming. No ready-made example springs to mind at the moment, but, depending on the context, he could make a word like "car" line up with "there" in one verse and "her" in the next, without allowing such enunciative license to undermine the structural foundation upon which his lyrics are built. T.I. takes this effect and applies it to whole lines, bending them at will. Plenty of rappers are "lyrical," in this sense of the word. 2Pac, Snoop Dogg, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony - all benefited from their sing-song styles. And "rapping to the beat" has been standard operating procedure since Wonder Mike. But T.I. does something extra. He doesn't rap over a beat so much as he raps in it. There's a peculiarly chameleonic quality to the way his voice takes on the shape of its surroundings, whether it's the sound of a Blaxploitation soundtrack ("King Back"), 90s dance club boilerplate ("Why You Wanna"), or the quiet storm of contemporary R&B ("Live in the Sky"). Perhaps his most impressive shape-shifting feat is coming off like the third member of OutKast, his fellow Atlantans, on "I'm Talking to You," where his pace on the last verse threatens to overtake the beat itself, having long since left most listeners behind. Grade: B+

#44 - Metallica's "Master of Puppets" (1986)

One of the body's cleverer mechanisms for dealing with the hubbub of the modern world is called sensory adaptation. Simply put, if it wanted to, the mind could try to process all the stimuli with which it is confronted every moment - the light and shadows that bounce around a room, the micro-weather patterns of a house, the sound of the blood pulsing in one's ears, the various points of contact where clothes meet skin - but, quite likely, such a constant barrage would be excruciating. Consequently, we adapt. I think something similar happens once we become immersed in a particular style of music. So inured do we become to certain elements that traits we might otherwise find grating if we were more aware of them tend to pass by relatively unnoticed. Just as the novice may be expected to miss the nuance of a style to which he is new, so may a devotee cease to notice features the outsider might find odd. Alexis de Toqueville's Democracy in America is a classic text primarily because, as a foreigner, he was able to perceive the United States of the 1830s with eyes unjaundiced by familiarity. It was this same attitude I tried to adopt when I approached the critically-acclaimed Master of Puppets by the seminal heavy metal band Metallica. So what did I hear that the native-born headbanger might have missed? Themes so comically dark it was hard for me to take them seriously. But, that's alright, because Metallica take themselves seriously enough for all involved. And the lyrics - oh, the lyrics! - they positively luxuriate in pain, death, insanity and violence, as if they were indulging in a shiatsu massage spa treatment...in hell. Not that I could focus on the words all that much as the vocals took a backseat to the cacophony enveloping them. Good thing, too, because otherwise I might've had to endure a greater intimacy with James Hetfield's groan-inducing, faux-medieval, German-style syntax on lines like "never you betray," "in madness you dwell," "nothing could I say," and "with fear you run." Read those out loud and it sounds like Yoda translating the diary of Vlad the Impaler. Several of the songs, most notably "Battery" and "Damage, Inc." begin softly and melodically before descending into the band's brand of sludgy thrashmageddon. Unfortunately, these are more fake-outs than they are forays into meaningful variety. For a band that thrives on compositional innovation, it comes off a bit lazy going to that same well time and time again. Still, this album reminds me of nothing more than it does classical music and that might be the proper context in which to view the band itself. These are highly adept musicians writing mini-symphonies that feature shifting time signatures and complex transitions all played at break-neck speeds. They are also stuck in arrested development, articulating puerile ideas and exuding an often amateurish theatricality. But is it so strange for these disparate qualities to coexist? If Amadeus is to be believed at all, Mozart was three parts genius, one part buffoon. Such a summary might also be applied to Metallica, even if their ratio is somewhat closer to 1:1. Grade: C

#43 - Buck Owens & His Buckaroos' "I've Got a Tiger by the Tail" (1965)

Like many others for whom Creedence Clearwater Revival provided the first introduction to the name "Buck Owens," I wasn't sure what to expect from the man himself. Given that John Fogerty's shout-out to his fellow Golden Stater came during "Lookin' Out My Back Door," one of CCR's happiest, hokiest, hillbilly-est hymns, I should've known. Both that song and the Buckaroos' Bakersfield batch are cut from the same cloth: short, sunny, and spry. Oddly enough that mood persists throughout I've Got a Tiger by the Tail, despite variation in subject matter. Even when Owens is getting his ass kicked by love ("Trouble and Me," "Cryin' Time"), the only thing that really seems to change is the tempo. It's telling that even though the third track is titled "Let the Sad Times Roll On" and the seventh is called "We're Gonna Let the Good Times Roll," there is no appreciable difference in his voice. Take a good look at that album cover (he sort of looks like a clueless Mel Brooks, doesn't he?). Maybe he's just an upbeat guy. You can't exactly fault him for that. And you wouldn't want him to manufacture the pathos you hear on so many other country albums. It's just that when it comes down to it, as a vocalist, he's not all that versatile. He comes close to that "high lonesome sound" on a couple of occasions, but ends up more high than lonesome. For the most part, when a song needs an injection of some feeling other than optimism, Owens relies on the dependably mournful pedal steel to do the heavy lifting. Likewise, some much-needed variation is supplied by "The Streets of Laredo" - a highlight - when bass player Doyle Holly takes over singing duty. You know, they say you can't keep a good man down. Perhaps you can't make an up man good. Grade: C+

#42 - Muddy Waters' "At Newport" (1960)

'Twas the daytime in Newport, the afternoon show

when a Delta-born bluesman stood rarin' to go.

The folkies had flocked from far and from near

in hopes he'd play blues they'd all come to hear.

The buttoned-down crowd nestled snug in their seats

(no visions of dancing to those big Chi-town beats)

and Muddy at the mic-stand, his band at his back,

broke full-throttle through with a sonic attack.

They jived just like butterflies, they stung hard like bees,

"I Got My Brand On You" had 'em all weak in the knees.

But then "Hoochie Coochie Man" started up soon

and the crowd - to a man - could not help but swoon.

The sun and the heat likely both took their toll,

but neither deprived the poor crowd of its soul.

No, that was Muddy's, his prize fair and square.

He scalped 'em with sweetness, with grit, and with flare.

With his band, he was lethal, so poised and so tight,

having logged all those hours in the juke joints each night.

In rope-a-dope fashion, he reeled in the fish,

called out their songs like he was granting a wish:

"Now, 'Tiger,'

Now, 'Mojo,'

and now, 'Soon Forgotten.'"

Their "I Feel So Good" made "O.K." look rotten.

To the end of the song!

To the end of the set!

With "Mojo" once more

(as if you could forget!)

His harp, how it zig-zagged! His keyboards, how jazzy!

His drums brought out big guns, so thund'rous and spazzy!

His speech between songs was humble, polite,

bringing black southern charm to the young northern white.

The lyrics he slurred and motorboat-barked,

and the axe in his hands - so electric it sparked -

sent currents through him, from his brain to his belly.

Ladies shook when he sang, like a roll full of jelly.

With "Goodbye Newport Blues," he got up and went.

Believe it or not, a half hour was spent

on just nine little songs, of which none was a dud...

...and that is how Newport got baptized in Mud.

Grade: A

#41 - Jimmy Reed's "Rockin' with Reed" (1959)

When it comes to the blues, "it all sounds the same" is a frequent refrain from the uninitiate. Of course, epithets like this wear the guise of considered opinion, as if, after exhaustive research, one has concluded that there is water, water everywhere but not a drop one would deign to drink. Jimmy Reed is especially susceptible to this type of critique, being such a populist purveyor of the blues. Yes, you'll hear those familiar twelve-bar chord progressions, for the most part played slow and steady. Reed is no virtuoso and never aims to "challenge" his listeners with experimental noodling or soaring solos. But don't confuse his genial, unambitious style with lack of talent or vision. What he seems to understand, maybe better than anyone, is that the foundational pattern of the blues was established not merely because of its simplicity, but rather its deep, abiding power. In the right hands it becomes the sturdy skeletal framework upon which the musician may hang the sustaining stuff of life. In Reed's hands, the way he adorns that skeleton becomes everything, which is what someone who thinks "it all sounds the same" will miss ten times out of ten. The most serious charge I can lob at this album, is that its title constitutes false advertising. "Rockin' with Reed" is the last track and it does, indeed, rock, but the rest of the songs here do everything but. There's his loving desperation on "A String to Your Heart," his penitence (and incorrigibility) on "I Know It's a Sin," his smirking sense of humor on "Take Out Some Insurance," and his smooth cool on "The Moon is Rising." The blues structure is limited and requires a kind of lyrical economy, so he wrings the most out of his lines when he throws in alliterative touches like "green grass grows" on "Down in Virginia." In the same song, he flexes his vocal range, finishing off each verse with a low, smoldering tremolo that hits like a haymaker every time. Blues like this teaches you to "see a world in a grain of sand," to love those tiny details, those little moments that make all the difference. Grade: A-

#40 - Gillian Welch's "Revival" (1996)

One of the great moments in Malcolm Gladwell's less-than-great Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking involves the elaborate forgery of an ancient Greek statue, the authenticity of which was confirmed by several scientific tests and denied outright and immediately by three art historians. The point Gladwell uses the anecdote to make is that oftentimes an expert's human hunch can trump the analyst's cold calculus. The point I'd like to make with the story is that the reason the statue befuddled those who studied it was that the form was right, but not the essence. Early Christian theologians made use of a similar distinction when they repurposed the Aristotelian taxonomy of matter to explain the mystery of transubstantiation. They argued that the characteristics of a thing (looking, feeling, tasting like bread) are quite separate from that essential quality that makes it what it is (the body of Jesus). All of this is my admittedly circuitous way of saying that Gillian Welch nearly had me fooled with the songs she wrote and performed on Revival. They sound in so many ways just like the old-timey material of the 1920s and 30s with which she is so thoroughly engrossed. The close harmonies, the mono recordings, the hard-luck tales of orphans, factory girls, moonshiners - if you didn't know better, you'd swear she had uncovered some dusty trunk of songs in Joe Bussard's basement. It seemed like Welch had figured out a way to contact the spirits of another time and place. And, to crib a line from Scooby-Doo, "she would've gotten away with it, too, if it hadn't been for this meddling listener." Everything seemed first-rate and pitch perfect until the sixth track, "By the Mark." I had been anticipating this song as it approached, hoping the title might be an allusion to Samuel Clemens. In it she sings, "When I cross over / I will shout and sing / I will know my savior / by the mark where the nails have been." Now, on the surface, this is the type of rustic gospel tune you might expect to hear from a Carter Family acolyte. It's got that reward-in-heaven theme, that humble evocation of Jesus' bodily suffering on the cross. You know, that good, ol'-fashioned blood of the lamb stuff. The only problem is the concept. As any holy-rollin', God-fearin', Bible-thumpin' Christian (or, in my case, 20-year veteran of Catholic schools) can tell you, it's highly unlikely that someone very familiar with the New Testament would say, "I will know my savior by the mark where the nails have been." To do so is a little too like calling oneself a "doubting Thomas," the pejorative term that refers to the apostle who insisted on confirming the identity of the risen Christ by feeling his wounds. This is also why you don't hear a lot of gospel songs that talk about "kissing Jesus," for fear of being associated with that most notorious of kiss-and-tellers: Judas, the betrayer. Am I being too picky? Probably. But I also think it's likely that Welch, who grew up in a secular household in New York and L.A., is more inspired by gospel music than she is by the religious feelings that produce it. Of course, none of this is to suggest she meant to perpetrate fraud or pass off her songs as anything other than a sincere homage to the Appalachian folk that so moves her. At Boston University I had the pleasure of working for, taking classes with, and attending lectures by the incandescently brilliant literary critic Christoper Ricks. In a lecture on "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll," much of which appears in his labor of love, Dylan's Vision of Sin, Ricks said there was a big difference between writing a political song and writing a song politically. The former requires little skill or imagination. Mention George W. Bush and you're halfway there. The latter, however, implies an ability to effect a particular response in your audience by the manner in which you write the song itself. I think the same goes for religious music, which is why "By the Mark" misses its mark. Welch has mastered the form. Now all she needs is the essence. Grade: B+

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)